We are very pleased to announce that our Founder and CEO, Lt Col (retd) Philip Holmes, has been appointed Officer of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (OBE) in the New Year 2023 Honours List. Philip's name has appeared on the Overseas and International List in recognition of his services to vulnerable people in Nepal. He hopes that this honour will provide a boost to this work, a milestone on a broad path that leads ever upwards.

Philip set out on that path just over 23 years ago after he paid his first visit to Nepal in November 1999. But his current activities and interests find their origin long before that as he explained in this informal CV that he prepared recently as part of a grant application:

"I was born in 1960 in Kilrea, a little village in rural County Derry, Northern Ireland. Rather like the poet Seamus Heaney, who grew up just eleven miles away, this engendered in me a love of nature, the wonder of which I came to know from a very tangible, sometimes leg-scratching, exposure. I would vanish off for the day into the countryside, bird-spotting or pond-dipping for a range of aquatic life that I could name thanks to the little "Observer's Book of Pond Life" that I kept in a hip pocket. I loved climbing trees (I could identify those all as well), to sit as close to the tops as I could manage, relishing the powerful wind-sway of a tree in full leaf.

I was good at school. Benevolent senior relatives would ask me what I wanted to be when I grew up. I would pipe up "conservationist", influenced as I was by my countryside ramblings and the exploits of Jacques Cousteau and David Attenborough. That didn't really compute with them. They'd smile indulgently and wonder aloud if I shouldn't go for a "proper" profession like becoming a teacher or a doctor. When I was in my teens and having to take that career choice, my elder brother, Willie, himself a doctor, counselled me against that particular profession. I remember his bizarre advice "You're good at art, Philip; why don't you become a dentist?"

With three "A" grades behind me in my 1978 "A" levels, I took a brother's dubious advice and joined Queen's University Belfast dental school for a four-year Bachelor's degree course. My time there was nothing much to write about, although I did show a certain flair for human anatomy. That was because rather than learning by rote the relationships of features to one another, I mastered their positioning through drawing, superimposing layer upon layer of tissue, nerve and blood vessel until I reached the surface.

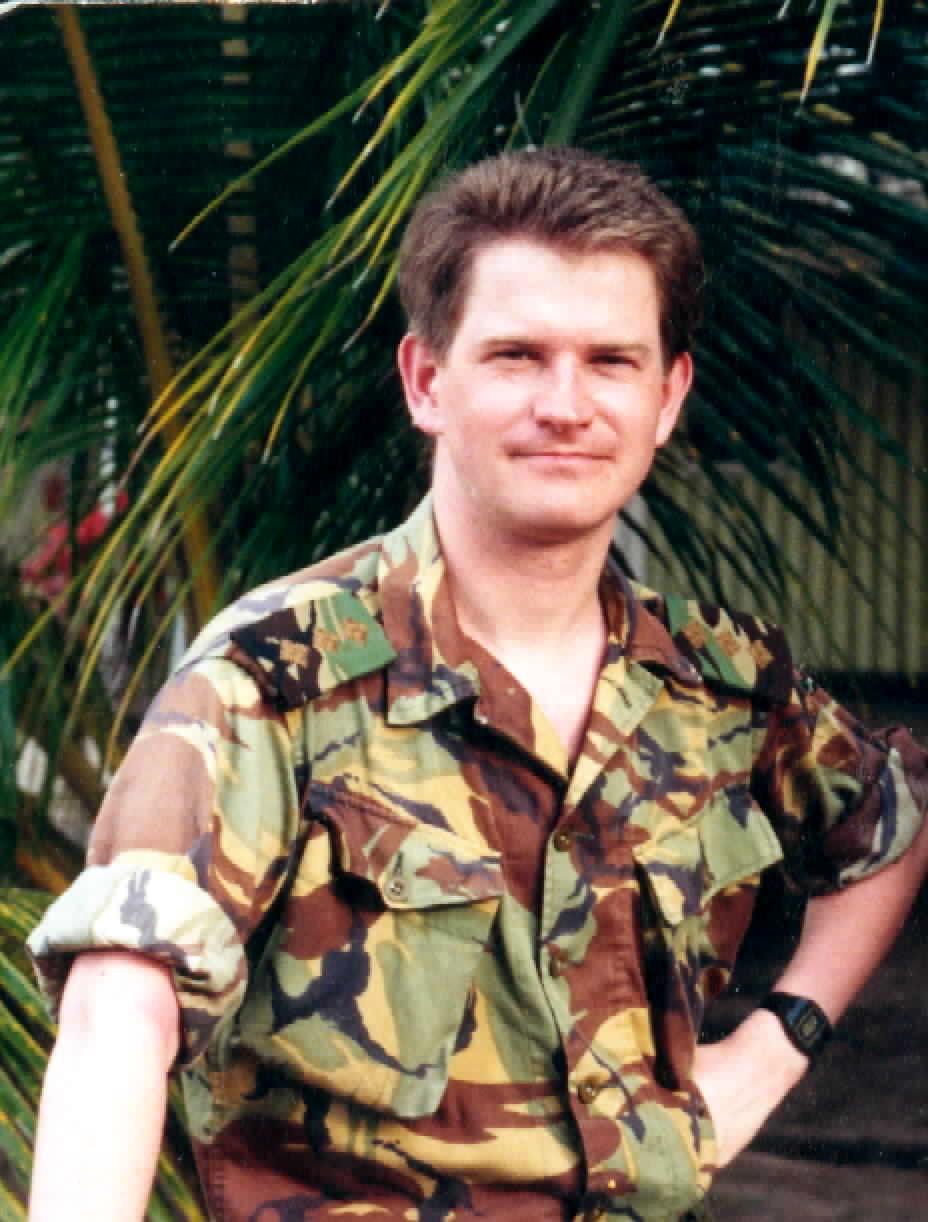

In 1982, aged 22, I decided that joining an NHS high street dental practice felt too much like potentially the start of a 40-year prison sentence. So, I elected for some excitement by joining the British Army, initially for three years. I didn't want to commit to more than that. When you're 22, even three years seems like a lifetime. Those three years became seventeen in the end as I discovered that the Army offered me a healthy variety with a regular change of scenery and postings as far afield as Germany, Inverness and Belize (pictured). I even "earned" a medal following a brief spell of duty back home in Northern Ireland.

In the Army I enjoyed a variety of employment with roles ranging from being a dental officer in a M.A.S.H.-type unit, to being an assistant anaesthetist in a field surgical team, to spending a fascinating three years as a desk officer at the Ministry of Defence. I was allowed space to study, taking a coveted higher diploma in my own time, followed in 1995 by a one-year MSc course at the University of London which I passed with Honours. This course fuelled an interest in scientific research, my thesis leading to the publication of a research paper in the highly acclaimed journal Dentomaxillofacial Radiology. These days, my name appears as a footnote in dental textbooks! In 1995 I was also promoted to the rank of Lt Col.

I married in 1988, my first wife being a Dutch Jew called Esther Benjamins. Professionally, Esther had been a social worker with the survivors of the Holocaust, before turning to study law in her spare time. Just before we married, she had passed her Masters in Law and in 1998 was appointed to the Judiciary. This professional success concealed an underlying sadness in that she had been unable to realise her main ambition of becoming a mother. In 1998 this led to a major downturn in her mental health and in January 1999 Esther took her own life at the age of just 43.

In the midst of that trauma and heart-break, I knew that I had to respond positively. Within days of the suicide, I had decided to leave the Army and dentistry and set up a children's charity to perpetuate Esther's memory and high ideals. I chose to work in Nepal where I felt that I could build "Esther's family" through helping vulnerable children. No one could have been more underqualified than me for such an undertaking - I had never even been to Nepal - but when I set my mind to do something I can be determined to the point of being stubborn.

My initial work with The Esther Benjamins Trust involved rescuing innocent children from Nepalese prisons, children who had been imprisoned alongside parents in the absence of anyone else being willing or able to care for them. I set up a refuge that could offer this care and in December 1999, at the end of that tragic year, brought my first seven children out of Kathmandu jail (pictured above). I continued this work over the subsequent months, prison by prison, freeing around 30 children, while at the same time raising awareness through the media. My work was covered in international papers ranging from The Boston Globe to the Melbourne Herald Sun. In July 2000 I was profiled as cover story in the Weekend section of the Daily Telegraph. This coverage led to an avalanche of support and effectively launched the charity. I like to think this adverse exposure shamed the Nepal government into taking action (although I cannot prove cause and effect) and in November 2001 the government outlawed the jailing of innocent children.

In 2002 I shifted focus onto child trafficking, my charity being the first to research a hitherto unknown issue - the trafficking of Nepalese children across the open border into India to become "performers" inside Indian circuses. The children became slaves, trapped in de facto prisons, subject to physical, psychological and sexual abuse. Eighty percent of the children were girls with an average age of eight. Having done the research, we decided to do something about it. In 2004 I moved with my wife, Bev, to live in Nepal, so that I could head up a programme of rescues. This involved crossing the border into India and, in conjunction with the Indian authorities, removing the children from the circuses. These highly dangerous operations led to freedom for 350 children with a further 350 released voluntarily by the circuses in their bid to avoid bad publicity and the risk of prosecution.

In 2006, following our legal action, a Nepalese court recognised the circuses as a trafficking destination and the first circus trafficker was imprisoned for 20 years. This set the legal precedent for a further 18 traffickers to be jailed. By the time of our last rescue in 2011, we were finding no Nepalese children inside circuses. That was because procurement had stopped (all the traffickers were in prison) and demand at the circuses had dried up.

In April 2011, the Indian Supreme Court responded to a petition submitted by our partner, ChildLine India Foundation, and ruled that children under the age of 18 could not be used as performers. This put the seal of sustainability onto our closure of a child trafficking route - an unprecedented achievement by myself and some very determined colleagues. It should be noted that we also managed the trafficking survivors very successfully. Some excelled academically and entered professions. We even formed our own circus group - Circus Kathmandu - that performed around the world, including at Glastonbury in 2014.

In November 2011, my team closed down a second child trafficking route - the trafficking of Nepalese children to an extreme "Christian" indoctrination centre in Tamil Nadu. This had been operated by the self-styled "India's Billy Graham" who was working with Nepal's biggest child trafficker, Dal Bahadur Phadera. In an extremely dangerous mission, we brought the children back to Nepal after a nine-year absence and exposed this fake-orphan racket nationally and internationally in the media. This included in The Daily Telegraph - "The Indian Preacher and the Fake Orphan scandal".

In 2012 I returned to the UK with my wife and two adopted Nepalese children. At this point, I decided that after 13 years it was time to leave this charity and allow it to develop along its own lines. It had very much served its purpose for me in commemorating Esther Benjamins through the closure of two child trafficking routes. Besides, I needed to take some time out to be with family, including elderly in-laws (since deceased) and to write my memoir, Gates of Bronze, that I published in 2019.

In 2015 I registered a new charity, originally called ChoraChori (Nepali word for "children"), to resume my charitable involvement in Nepal. With time, this name soon became redundant as our initial work tackling child rape evolved into supporting all female survivors of sexual abuse. We had also provided community support during the earthquake of 2015 and the floods of 2017. But above all, by 2020 I had become preoccupied by the climate emergency .

So, under the new name of "Pipal Tree", we called a "Decade of Action" for the planet and began restoring the natural environment and forests in south Nepal, with the goal of planting 1,000,000 trees by 2030. I am presenting this to donors as a series of projects whereby public art is juxtaposed with reforestation. At the heart of this programme lies community engagement that supports the most vulnerable ethnic groups and women.

The first of these launched in December 2021 at the Dhanushadham Bird Park where we are pioneering the Miyawaki Method of rapid reforestation. This is designed to attract endangered species of birds to what had been a piece of degraded, over-grazed public land while at the same time attracting tourists to see these and the bird mosaics I have made to be sited around the perimeter of the plantation.

My second project, launched in May 2022 and running concurrently, is a Gurkha Memorial Forest Park where a ten-year tree planting programme will take place alongside the construction of a large mosaic mural dedicated to the Gurkhas. It will be a living memorial to the 120,000 Gurkhas who served in the Indian and British Armies in the Second World War and particularly to the thirteen Gurkha heroes who have won Victoria Crosses since 1939. What better way to capture carbon?!

On a visit to Nepal in February 2022 I was invited to speak to an English class in a school in the east of the country. My message to these young teenagers, for whom the climate crisis really will be an existential threat, can be distilled as follows:

- Cling to your childhood dreams and aspirations - finally, at the age of 62, I find myself as both a conservationist and an artist.

- Don't pursue money. There are more rewarding things to do in life.

- Never be overwhelmed by the scale of a challenge, believe that you're underqualified or told by "experts" that it can't be done. Just make a start and be prepared for the unexpected that will amplify your efforts.

- The solution to the climate crisis is already before us; it lies in the human aptitude for scientific discovery and creativity.

Maybe these children will remember my visit and be inspired, as I once was by David Attenborough and Jacques Cousteau."

If you would like to help Philip along at the start of this most challenging of years, you can join him in becoming a "first-footer" to Pipal Tree using the button below. Thank you and Happy New Year!

.png)

.png)